A year ago, it seemed like Covid might finally have been the one opponent powerful enough to thwart fast fashion, the category known for inexpensive and cheaply made “disposable” garments. Headlines opined about fast fashion’s end: lockdowns lead to a slump in demand for new clothes, garments were stock piled in warehouses and consumers suddenly seemed to realize they didn’t need new clothes every other week. Designers welcomed the idea of not competing with fast fashion’s endless deliveries. Regularly, it seemed, talk focused on better quality, better working conditions and a more sustainable fashion industry.[quote]

Cut to last month, and the Wall Street Journal’s article on Shein, which shone a light on the Chinese ecommerce fast fashion retailer that has become a darling among young consumers.

Now, it should be noted that 64 percent of all fashion shoppers, and most consumers under the age of 35 (54 percent), say they would rather buy clothes that are higher in quality than more fashionable, according to the 2021 Cotton Incorporated Lifestyle Monitor™ Survey. And more than one-third of all shoppers (35 percent) say sustainability and environmental friendliness is important to them when deciding on what clothes to purchase. Further, the majority says cotton clothes are the most sustainable (78 percent), highest in quality (71 percent), and last the longest (56 percent) when compared to manmade fiber clothing.

Perhaps knowing consumers have these interests and preferences, Shein has a whole page on its website devoted to “Our products/Our planet.” Here, it talks about sustainable fibers and production, remarking that it makes some use of deadstock synthetics and only produces 50-to-100 pieces of each new product, which sounds reasonable. Until, for example, one clicks on, women’s clothing, and there are 229,530 products ranging in price from $2 (for, say, a bodycon skirt or halter top) to $146 for a down coat that converts from full- to waist-length. It also offers more than two-and-a-half times the number of clothes made from man-made fabrics as it does from natural fibers like cotton, silk, and wool (462,406 products versus 173,918).

In a report, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) found 60 percent of all apparel is made from synthetic fibers. Further, the IUCN report says 35 percent of the microplastic pollution in the world’s oceans comes from washing synthetic textiles in household laundry. The tiny microfibers shed from manmade fibers like polyester, which are discharged in the wash cycle and have been discovered in lakes, rivers, oceans — even tap water. This is the case whether it’s virgin polyester or spun from recycled bottles.

Recycled plastic apparel has gained some support in recent years. But it will not be making its way into the collections of Ron Poisson, the co-founder and designer of the premium denim and sportswear brand Cult of Individuality, as well as HVMAN, the brand’s new upscale line of streetwear.

“Sustainability and environmental issues are obviously very important,” Poisson said before his Spring ’22 runway show in New York in an interview with Lifestyle Monitor™. “We haven’t gone into any type of recycled bottle apparel pieces. We’re very conscientious about the environment, though. Denim manufacturing was a problem environmentally so, because I’m partners in factories in Asia, we’ve been working to change that. We have ozone machines we’re buying (for sustainable washing effects) and laser machines so people aren’t sandblasting and hand sanding. It’s more environmentally friendly and also friendly to the workers.”

“Unfortunately, there are a lot of people using the recycled plastic, not because they’re trying to be environmentally friendly, but they’re trying to do a marketing job like greenwashing. That’s not my thing. I’m not using that as a way to convince you to buy more from me. I’m just doing that as a personal effort, so I know what I’m doing is contributing to other people on a greater scale,” said Poisson.

But fast fashion brands don’t shy away from promoting sustainability on their websites. For example, of the 25,000-plus items PrettyLittleThing offers on its site, 366 are made from recycled fabric.

Veteran fast fashion brands H&M and Inditex (Zara) recently signed the International Accord for Health and Safety in the Textile and Garment Industry, which was appreciated as a small step for the industry by Maxine Bédat, founder and director of The New Standard Institute, an environmental and sustainability non-profit for the fashion business.

“This is very far from solving the problems associated with fast fashion but it shows a serious, legally binding commitment to make improvements in a specific area (building safety),” Bédat says in an interview with Lifestyle Monitor™. “The newer crop of fast fashion players — Boohoo, PrettyLittleThing, Shein — has made no such commitments. This does not paint a picture of an industry that has evolved. In fact, it shows a sector that is entirely unhinged; a fossil fuel-driven industry, producing disposable garments with little to absolutely no regard to the impact they have on the planet or the people making and distributing them.”

And those brands flourished since the pandemic began. Charles Zhong, CEO of Azazie, the online bridal retailer, launched the sportswear label Blush Mark during the shutdown, since weddings and special events were cancelled. Glossy reported last year that the newcomer saw sales grow 200-to-300 percent every month since its launch. The Atlantic reported that ultra fast fashion brands Asos, Boohoo, and PrettyLittleThing all experienced significant growth during last year’s shutdown, especially since they didn’t have to contend with the hindrance of brick-and-mortar locations.

“In times of crisis, consumers don’t stop shopping,” the article stated. “They just limit their purchases to affordable pleasures.”

With the help of major players like Zara, H&M, Uniqlo, and Primark, the global fast fashion market is expected to grow from $25.09 billion in 2020 to $30.58 billion in 2021, according to a report from Research and Markets. It is expected to reach $39.84 billion in 2025. The report attributes the growth in the market to young consumers who are “attracted to unique, trendy and affordable clothes.”

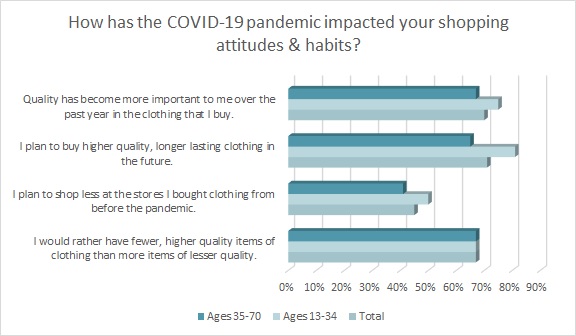

This appeal among shoppers under the age of 35 is ironic, considering that among those aged 13-to-34, nearly 7 in 10 (67 percent) say they would rather have fewer, higher-quality clothing items than have more items of lesser quality, according to Monitor™ research. Additionally, 75 percent say quality has “become more important to me over the past year in the clothing that I buy.” This is significantly higher than the percentage of those aged 35-to-70 who feels the same way (67 percent).

Still, when asked where they buy most of their clothes, Gen Z and Millennial shoppers choose fast fashion stores notably more than their older counterparts (11 percent versus 2 percent), according to the Monitor™ research.

This shopping behavior doesn’t look like it will end with the pandemic, either, as the majority of consumers under the age of 35 (65 percent) say they plan to shop for clothes at places like Zara, H&M, and Uniqlo just as often (48 percent) or more (17 percent) than before Covid struck, according to Monitor™ data.

Certainly, modern life has played a part in the choices young shoppers are making. The London-based environmental charity Hubbub found that 41 percent of 18-to-25 year olds feel the need to wear a different outfit every time they go out. Worse, 1 in 6 don’t feel they can’t wear an outfit again once it’s been seen on social media.

As Patsy Perry, senior lecturer in fashion marketing at the University of Manchester, said in a United Nations article even before the Covid shutdown occurred, it would be unrealistic to expect consumers to stop shopping on a large scale.

“Going forward, I would expect to see more development and wider adoption of more sustainable production methods.”