Capsule collections. One-offs. Affordable couture collaborations. They are all products of high/low collaborations, but what used to seem unquestionably bankable has recently hit a few snags. This retail formula has not jumped the shark, though. As consumers have become more sophisticated about finding bargains and recognizing value, such pairings just require more finesse — and perhaps the help of some data mining.

[quote]One of the most anticipated collaborations occurred over the holidays, when Neiman Marcus and Target rolled out a limited edition collection of apparel and household products, designed by 24 different designers. But sales lagged early and the venture did not come close to expectations.

Betsy Csatorday is senior vice-president/strategy director at atelier-lb, Leo Burnett Group’s luxury, beauty and fashion agency, which recently released a study entitled “The Affluent Bargain Hunter.” She says several points drove the downfall of the Neiman Marcus/Target mashup.

“Unlike the successful collaborations of the past, this was between two retail brands, rather than between a retailer and fashion brand,” Csatorday explains. “Additionally, the products in the collection were not in the same categories as the halo brands’ own products. As a result, the proposition wasn’t very clear for consumers.”

Furthermore, she adds, consumers did not believe the quality of the products matched their prices.

In general, 44% of U.S. consumers say the quality of apparel has decreased compared to last year, according to the Cotton Incorporated Lifestyle Monitor™ Survey.

Meanwhile, 79% of U.S. consumers are “very or somewhat concerned” about a reduction in their annual household income, so price is an important factor in apparel purchasing decisions for 92%, the Monitor shows. But they do not want cheap, shoddy clothes. They are looking for value, which is why 92% say quality is equally important in their decision to buy.

In this effort to save money, the greatest percentage of consumers buy most of their clothes at mass merchants (24%), including 11% of those making $75,000 or more, according to Monitor data. But the biggest percentage of high earners shop mostly at chain stores (27%), department stores (21%) and specialty stores (17%).

Another recent high/low collaboration that did not fly off shelves as fast as hoped was that between avant garde Belgian designer Maison Martin Margiela and H&M. Many of the items ranged from $200 to $400, compared to H&M’s usual pricing of under $100. That was too expensive, Csatorday says.

“There is likely a price point at which a Target or an H&M overreaches in the mind of the affluent bargain hunter, where, no matter who designed it, nothing from [that store] can be good enough to be worth that price.”

Csatorday says almost 80% of affluent bargain hunters shop at Target — more than those who shop at TJ Maxx (46%) or Neiman Marcus Last Call (14%).

“Affluent bargain hunters are very educated shoppers and know good — and bad — quality when they see it. On these [Neiman’s/Target collaboration] products, the value proposition wouldn’t have passed their test.”

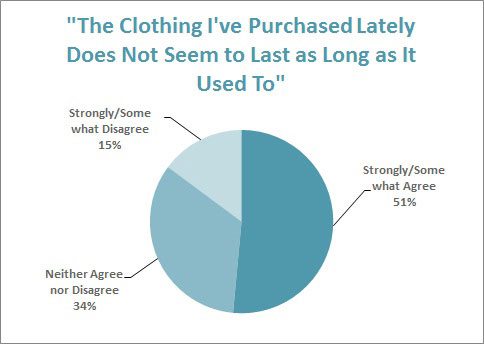

Currently, 43% of consumers say they are willing to pay more for better quality apparel, up from 41% a year ago, the Monitor shows. And more than half (52%) say the clothes they have purchased lately do not seem to last as long as they used to.

After the holiday dust cleared, Stephen P. Dennis, a former strategist and corporate marketing executive for Neiman’s, wrote in his blog that even if the collaboration did not work, it was something from which to learn.

“If it strengthens their resolve,” he wrote, “if they apply their learning to improve the process of innovation, then it will be the most glorious of failures.”

IBM knows one way retailers can offset the unknown variables involved in such collaborations. Jill Puleri, global retail leader for IBM’s global business services, says the company’s sentiment analysis can guide retailers in what will be trending, perhaps years in advance. Its Social Sentiment Index uses advanced analytics and natural language processing technologies to analyze large volumes of social media data in order to assess public opinions.

“These technologies allow us to comb the Internet and find certain key trends,” Puleri says, explaining, “The analysis starts with ‘Are there words that are going together that normally don’t?’”

Puleri says that with the social monitoring that exists today, IBM can train technology to go out and report on all the consumer sentiment regarding two particular brands.

“We can see what words are associated with everything from blog posts, Facebook posts, tweets, audio, video — and you measure the sentiment to see if it’s good or bad,” Puleri notes. “And for a lot of social monitoring tools, the amount of data is huge. Beyond that, we can leak information on a collaboration within a certain geographical area and listen to consumer appeal to see if it causes a stir. Even further, we can use data that identifies top influencers, so brands can reach out to them and ask questions like, ‘What if we did a collaboration with so-and-so?’

“It’s adding science to the art of retail, versus just trying to leverage your contacts.”