Imagine a large cruise ship, as tall as a 16-story building and longer than a city block. Next, imagine it’s made of tiny microplastic particles that suddenly collapse into the water, the teeny bits swirling, spreading, and sinking. The non-biodegradable particles land on the ocean bottom, are eaten by aquatic animals, and enter our food chain, or find their way into our drinking water.[quote]

If this scenario happened once, the world would likely be aghast. But picture it occurring every year, with no end in sight. That’s basically what’s happening with clothes made from synthetic fabrics like polar fleece, acrylic, and polyester. And it might inspire the apparel industry to think about using more eco-friendly natural fibers heading to World Water Day on March 22.

If the cruise ship correlation seems far-fetched, consider that as much as 0.19 million tonnes — the equivalent of almost 209,000 U.S. tons — of microplastic pollution from apparel production, usage, and laundering enters the environment every year, according to a journal article in Science of The Total Environment entitled “Microfibres from apparel and home textiles: Prospects for including microplastics in environmental sustainability assessment.” For comparison’s sake, the popular Norwegian Escape cruise ship is 164,600 tons and Royal Caribbean’s mega Symphony of the Seas, which is nearly four football fields long, weighs 228,081 tons.

This enormous amount of synthetic textile-related pollution makes sense considering up to 700,000 microplastic particles can be released into the environment during every laundry cycle, according to a University of Plymouth study.

Further, the authors of the Science of the Total Environment article determined that plastic microfibers and nanofibers comprise up to 35 percent of microplastics in marine environments.

“Plastic production increased from about 1.7 million tonnes in the early 1950s to more than 310 million tonnes in 2015,” says Dr. Beverley Henry, associate professor at the Institute for Future Environments, at Queensland University of Technology in Australia, and one of the authors of the study. In the interview with Cotton Incorporated, she continued, “However the exponential rise in waste including synthetic microfibers from apparel and textiles started around 2000 with ‘fast fashion’ — around the same time polyester overtook cotton in fiber production.”

Nearly a third of consumers (30 percent) are aware of microplastic pollution, according to the 2020 Cotton Incorporated 2020 Lifestyle Monitor™ Survey. That’s an 11 percent increase from last year, and a 76 percent jump from the 17 percent who were aware of it in 2017.

This awareness is significant, as 75 percent say knowing about microfiber pollution will affect their apparel purchase decisions, according to the Monitor™ research. More than 6 in 10 (62 percent) say after learning about microplastic pollution, they’re bothered that brands and retailers are using synthetic fibers in their clothes.

Additionally, after learning about synthetic micro-particle waste, more than half of all consumers (56 percent) will likely check the fiber content label before purchasing clothes to avoid those made from fibers like polyester, acrylic and nylon, according to the Monitor™ data. That number significantly increases to 64 percent among Boomer shoppers. And nearly three-fourths (73 percent) of consumers seek out clothes made from sustainable, environmentally-friendly or natural materials at least some of the time.

The theme of World Water Day 2020 is focused on water and climate change. Organizers want climate policy makers to put water at the heart of action plans. They are also promoting that “anyone, anywhere” can take water actions to address climate change.

Consumers might not yet be aware of the double whammy microfiber particles have on the environment. Besides polluting water bodies, and entering both the food chain and drinking water, a study from the University of Hawaii at Manoa found that microplastic pollution contributes to climate change. The team found that when plastic is exposed to sunlight, it releases methane and ethylene, both of which contribute to global warming.

“Because polyethylene is the most common polymer, it is anticipated to be the most common form of plastic pollution in surface ocean waters worldwide,” the University of Hawaii study states. “In addition, as microplastics with greater surface area are produced, hydrocarbon gas production rates will likely accelerate.”

Dr. Henry, along with Kirsi Laitala, senior researcher, and Ingun Grimstad Klepp, a research professor, both at Consumption Research Norway at Oslo Metropolitan University, also performed a study that focused on microfibers from synthetic textiles to see whether it was possible to “define an indicator to guide early action to reduce future harm.” The team concluded there is no simple solution to eliminating the risks of microplastic waste.

“All actors in each segment of the complex plastic supply chain need to share responsibility,” the team wrote. “For the textile industry, we propose options that include reducing consumption in total, changing laundry practices to decrease release of synthetic fibers and increasing the share of natural biodegradable fibers. These actions are possible now.”

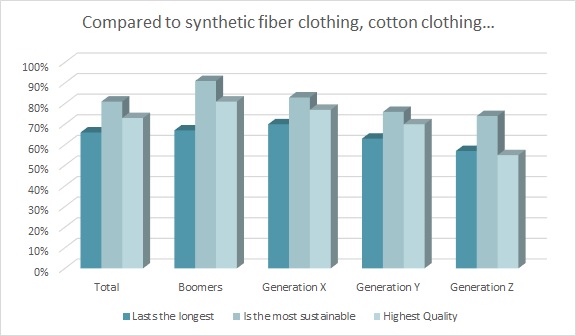

It may be a wise move for the industry to start using more natural fibers. Already, 81 percent of consumers say that compared to synthetic fiber clothing, cotton apparel is the most sustainable, according to Monitor™ research. Further, 73 percent say cotton clothes are the highest quality and 66 percent say they last the longest.

Some fashion brands are turning to textiles made from recycled plastic bottles. While this is giving the bottle new life, the apparel ends up having the same ill effect on the environment as any other petroleum-based textile. And as Claire Arkin, communications coordinator for the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, told the Yale Climate Connections, “We can’t recycle our way out of the plastic pollution crisis. There’s simply too much plastic – single-use plastic – being produced and consumed.”

Which is why Henry advocates for using more natural, biodegradable textiles in the Cotton Incorporated interview.

“In terms of microfibers, there is little doubt that all textiles — whether natural or synthetic — shed during production, use and disposal,” she says. “But there is credible evidence that fibers of wool and cotton biodegrade in ocean water due to the action of naturally occurring microbes such as bacteria and fungi to produce harmless molecules that are used again in natural ecosystem cycles. On the other hand, plastic microfibers persist for many, many (possibly hundreds of) years.”