“Out of sight, out of mind” could easily describe the problem facing America’s waterways, marine life — and our own health, as well. It’s happening via an unwitting cycle, but one that may be broken by a collective move toward natural fibers.[quote]

A recent TV news report by New York’s WCBS said people’s gym clothes could be dangerous to our health, due to the apparel’s fibers. The garments’ manmade fabrics break down in the laundry, forcing the lint fibers to wash out into public waterways and attract pollutants, which are then are eaten by fish — fish that we consume.

The WCBS report comes after another finding by ecologist Mark Browne, who examined shorelines around the world and found microfibers everywhere, particularly near sewage outflows. His finding, according to a report in The Guardian: 85 percent of human-made material on the shorelines were microfibers, and matched manmade clothing materials like nylon and acrylic. While the WCBS story focused on gym clothes, synthetics have found their way to virtually every category of men’s, women’s, and children’s apparel.

Of course, cotton apparel can break down into micro-particles as well. In a paper that studied the deterioration rates of different fibers in outdoor situations for use in forensic studies, Kellie Marie Gordon, then a student at the College of William and Mary, found that in a period of 7 months, a 100% polyester sample saw minimal deterioration, while a 100% cotton sample had 100 percent disintegration.

The effects of aquatic environments on cotton apparel fibers is not currently known, but Cotton Incorporated is commencing work with researchers at North Carolina State University to better understand it. Mary Ankeny, Senior Director of Textile Chemistry Research at the company explains that the two-year study aims to determine what happens to cotton fibers when they are released during home laundering.

“We hope to answer questions like where do these fibers go? Do they break down? If so, how quickly and completely compared to their synthetic counterparts,” says Ankeny.

Although the answers to such questions are of interest to consumers, price, style and fit rise to the top of purchase drivers for consumers.

“First, people have to love [the item] on them,” stated designer Margaret O’Leary recently at the Coterie Show at the Manhattan’s Jacob Javits Center. “In certain places, they might really care about the fiber. They might ask what it’s made of or where it was made.”

O’Leary’s sentiments echo findings by the Cotton Incorporated Lifestyle Monitor™ Survey, which found that before making an in-store purchase, the majority of consumers check the price (85 percent), try it on (74 percent), and touch the garment to see how it feels (70 percent). It is interesting to note that according to Monitor™ data, consumers are more likely to check fiber content when shopping online than in a brick-and-mortar retail environment.

Another Monitor™ finding may explain the reason why: About a quarter to a third of consumers have difficulty with labels themselves, such as the font being too small (36%) and there being too much information on fiber labels (26%).

Andie Verbance is owner of the multi-label By Land And Sea showroom in Los Angeles, which counts Benjamin Jay and SIR the Label among its brands. At the Coterie show, she related that customers do seem to like knowing if something is made of a natural fiber. However, she says, if buyers do look at apparel labels, it’s mostly to determine ease of care, followed by where it’s made and then the fiber content.

“Benjamin Jay does have natural fiber in its collection, but we don’t promote it the way we do for SIR, where we say ‘Most of these garments are made of natural fiber.’ But we don’t advertise if something is made from poly, because it’s not great for the environment,” Verbance says.

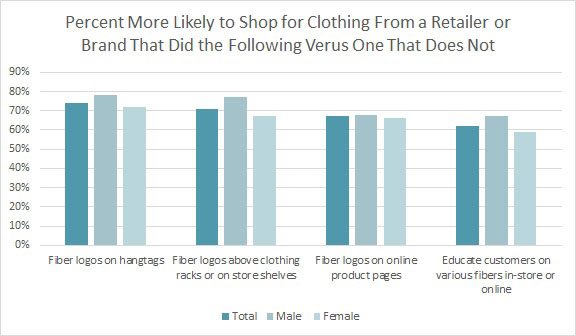

Consumers definitely prefer natural fibers, with nearly three quarters saying they’re better quality than synthetics, according to the Monitor™ data. For online and traditional retailers, opportunities exist to make fiber content information easier to find for consumers. According to the Monitor™, about 7 in 10 consumers say they would be more likely to shop at a store that uses fiber logos on clothing hangtags (74%), clothing racks or shelves (71%), and online product pages (67%).

Brands that would like to appeal to consumers’ environmental concerns while giving them their fabric of choice might explore Cotton Council International’s Cotton Incorporated’s Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of cotton fiber. The LCI reveals the energy, environmental and material inputs needed to produce cotton. The LCA draws on the LCI data to show the environmental impact a cotton garment has from field through to consumer care, use and, finally, disposal (cradle-to-grave).

Content labeling is the law, enforced by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection and the Federal Trade Commission. But labels only need to show the fiber content, country of origin, identification of the manufacturer, importer or other dealer, and care instruction. There isn’t any rule relating to fiber degradation or decomposition. So that’s up to brands to promote — or consumers to find out.

“The more educated consumers are on landfills and how much polyester is damaging the environment,” Verbance says, “the more people will pay more attention to it, for sure.”