If the U.S. and China were to post their relationship status on Facebook, the “it’s complicated” option comes to mind. [quote]

For decades, American businesses have taken advantage of lower production costs to have their goods made in China. More recently, as that China’s consumers gained more personal wealth, U.S. brands and manufacturers looked to not just have their product made there, but also purchased by its residents.

But when President Donald Trump pulled the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), President Barack Obama’s signature trade agreement, those in the apparel industry were keenly aware of a potential power shift.

The National Retail Federation’s Jonathan Gold, vice president for supply chain and customs policy, said trade with China, as well as other markets, is extremely important for the retail industry.

“China continues to be one of the top trading partners for the U.S.,” he says, explaining, “China is critical not only as a sourcing destination, but as a growing market for U.S. retailers and U.S. products. A strong economic relationship between the U.S. and China is important for a wide variety of economic and security reasons.”

Although China’s economy has slowed in recent years, it is projected to more than double (+102 percent) over the next 14 years from 73 trillion RMB in 2016 to 147 trillion RMB by 2030, according to Euromonitor International. In addition, apparel spending is also projected to more than double (+111 percent) from 1.8 trillion RMB in 2016 to 3.9 trillion RMB over the next 14 years.

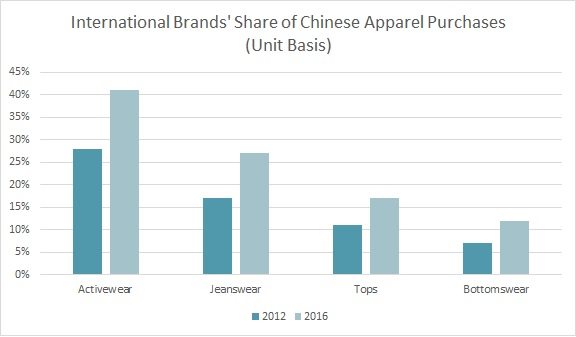

But to Gold’s point, China has been expanding its purchase of international brands. Significant increases have already taken place across a number of categories according to Cotton Council International (CCI) & Cotton Incorporated’s 2016 Chinese Consumer Survey. For example, in the activewear category, international brands accounted for 28 percent of Chinese purchase units in 2012, but that jumped to 41 percent in 2016. In jeanswear, international labels jumped from 17 percent to 27 percent, while tops increased from 11 percent to 17 percent in that four-year period.

In Tier 1 cities, growth in international brand purchase units increased from 10 percent in 2012 to 23 percent in 2016, according to the CCI & Cotton Incorporated Survey. Tier 2 saw an 8-percentage point increase from 7 percent to 15 percent. Tier 3 grew from 5 percent to 12 percent and Tier 4 saw substantial growth, from 3 percent to 15 percent.

Fast fashion brands H&M, Uniqlo, Zara, etc., account for 27 percent of the international brands purchased in China in 2016, up from 16 percent in 2012, according to the CCI & Cotton Incorporated study. That was followed by activewear brands (Nike, adidas, Puma, etc.) at 25 percent, down from 30 percent in 2012; jeanswear brands (Levi’s, Lee, Jeans West), etc.) at 22 percent, down from 26 percent; and Hong Kong-based brands (Giordana, Baleno, etc.), which increased to 18 percent, up from 15 percent four years prior.

At the China Market Research Group (CMR), Jason Lee, business analyst, says trade between China and the U.S. might be quite different in 2017.

“If the U.S. imposes high tariffs on Chinese goods, millions of Chinese workers would lose their jobs and China’s economic growth may be dragged down since China’s economy still heavily relies on exporting,” he says. “If the U.S. manufactures those goods by themselves, higher prices of the final goods may lead to higher inflation in the U.S. as a result. Also, the expectation of increasing the U.S. interest rates will pull the capital out of China to the U.S., which will lower the currency rate of RMB.

“To defend from the trade war, China’s government will keep its easy monetary policy and stimulate domestic investment rates or even impose higher quota or tariffs on U.S. imported goods or higher taxes on U.S. companies in China,” Lee continues. “Some U.S. manufacturing companies in China may start to relocate their plants to other Asian or developing countries because China will no longer be cheap for them.”

The United States Fashion Industry Association (USFIA) did a study last fall prior to the presidential elections — and so prior to the U.S. abandoning the TPP agreement — that found 100 percent of respondents did some sourcing from China in 2016. Although 61.5 percent expected to reduce sourcing from China in the next two years, only 4 percent expected a strong decline. Additionally, all the respondents source textile and apparel products that contain inputs from multiple countries.

The USFIA study respondents use “China Plus Many” for their sourcing. The study says 77 percent say “Made in China” accounts for less than 50 percent of their company’s total sourcing value or volume.

“In terms of the ‘Many’ part, Vietnam and other Asian countries typically account for less than 30 percent of a company’s sourcing portfolio, while most other countries account for less than 10 percent,” the USFIA report states. “Fifty-two percent of respondents source from the United States, with no change from last year. ‘Made in USA’ typically accounts for less than 10 percent of a company’s sourcing portfolio, and the companies do not see ‘Made in USA’ a major replacement for ‘Made in China’.”

Of course, Mr. Trump pulled out of the TPP in an effort to boost Made in USA product. But for China, this could be viewed as a trade win. It took more than five years for the Obama administration to pull together the TPP agreement. It involved 12 nations — but excluded China, as China is already seen as growing in influence. The 12 nations that were involved generate 40 percent of world trade. The TPP was meant to anchor U.S. presence in the developing region.

The U.S. currently has individual trade agreements with six of the TPP member countries. But it would have to hammer out one-on-one free trade agreements with the rest, a process that could take years. Meanwhile, China has been steadily working on a rival trade deal that covers more than half the world’s population — the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

“With the U.S.’s exit of TPP, countries like Japan and Australia may be more interested in the RCEP agreement,” CMR’s Lee says. “The negotiations of RCEP may face obstacles as some RCEP members have not established free trade agreements with each other, such as Chinese and Japan, Chinese and India. Whether these countries can reach consensus on the free trade agreement will determine the future of the negotiation of RCEP. Moreover, the political contradictions between the RCEP member countries are more prominent than TPP countries, as most RCEP members are developing countries. Competition and great friction in economy and politics as well as historical issues and territorial disputes may become barriers to the final agreement of RCEP.”

Gold says there is concern that China might conclude the RCEP before the U.S. can reach bilateral or multilateral deals in the Asia Pacific region.

“The benefit of the TPP was that it was led by the U.S. and brought U.S. standards into those trade negotiations,” Gold says. “The ongoing question is do we want China writing the rules of the road for trade or the U.S.? We clearly think the U.S. should be leading the way on these multilateral trade negotiations.”