Nobody likes feeling tricked, least of all consumers. Which is why government officials are making sure apparel manufacturers know that rayon, by any other name, is still rayon.

Recently, Amazon, Leon Max, Inc., Macy’s, Sears and its subsidiaries Kmart and Kmart.com agreed to pay $1.26 million to settle Federal Trade Commission charges that they were selling apparel that was marked as bamboo, but was actually made of rayon.

[quote]Korin Felix, staff attorney for the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, says as a general matter companies must comply because not only is it the law, but it is also important for consumers to know what is in the textiles they purchase.

For starters, it affects costs and care,” Felix says. “Also, some people have a philosophical reason for wanting all-natural fibers. Some people have allergies. Some people are buying for their babies. And some people want to know the fiber content because they’re interested in green product. The point is to give them the information to make that choice. The way the rules and the law work is you have to disclose that to the consumer because they can’t tell the difference just by feeling the fabric.”

Almost two-thirds (59%) of consumers say they would be bothered if they found out an apparel item they purchased was not produced in an environmentally friendly way, according to the Cotton Incorporated Lifestyle Monitor™ Survey.

On top of being bothered, 40% of shoppers would turn around and blame the manufacturer if they found out their clothes were produced in a non-environmentally friendly way, according to the Cotton Incorporated 2013 Environment Survey.

Elizabeth Cline, journalist and author of “Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion,” says both consumers and retailers are to blame for what is on the shelves.

“When the economy went bad, consumers became cheaper and cheaper, and stopped looking for quality — so retailers stopped selling it,” Cline says. “Everyone chases the low price point, and it’s difficult to resist.”

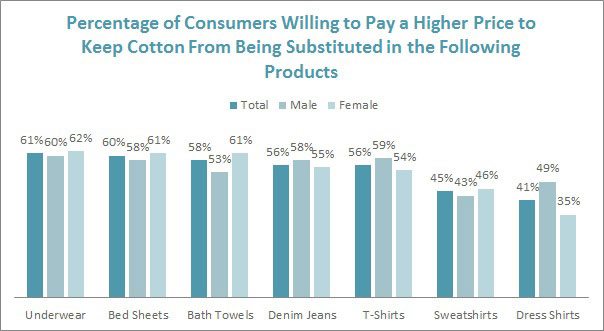

Retailers and brands who are thinking of using substitutions should know 82% of consumers prefer apparel be made of cotton and cotton blends, according to Monitor data. And they are willing to pay a slightly higher price to keep cotton from being substituted with synthetic fibers in their underwear (61%), denim jeans and T-shirts (56%), sweatshirts (45%), dress shirts (41%) and casual pants (37%), the Monitor shows.

James Dion, retail consultant and author whose titles include “The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Starting and Running a Retail Store,” says the apparel industry has to keep in mind that there will always be a “slash and trash” consumer who “shops price first, second and third. It’s their main component. And I believe there are more of them out there now who were driven by tough times.”

When cotton prices rose a few years ago to historically high levels, some brands and merchants started substituting it with other materials to keep prices in check. But when supplies stabilized, so did prices.

Consumers have consistently made it clear they do not want man-made fibers standing in for cotton: 77% agree better quality garments are made from all natural fibers such as cotton, up from 74% in 2011, according to the Monitor. And more than half (55%) say they are willing to pay a premium for natural fibers like cotton, an increase from 52% in 2011.

When brands actually do switch out fibers, consumers take note. Nearly half of all shoppers (49%) say many of the clothes that used to be made from cotton now seem to be made from other fibers, consistent with responses in October 2011 (48%). Additionally, more than six out of 10 are concerned that retailers and brands may be substituting synthetic fibers for cotton in their underwear (63%), tees (63%) and jeans (63%).

Felix says this is why the Textiles Act exists. “This is information consumers can’t obtain on their own. And that’s why it’s important it’s provided up front and not misleading.”

In 2009, the FTC brought its first set of cases against companies allegedly selling rayon textiles labeled as bamboo. In January 2010, the agency sent warning letters to 78 companies, including Amazon, Leon Max, Macy’s, and Sears, concerning their continued mislabeling of rayon textiles as bamboo.

Bamboo claims have been the most rampant. But Felix says manufacturers have professed to have manufactured clothes they say are made from soy, coconut, and even corn.

“People don’t wear corn kernels, soy beans or coconuts — unless they’ve been to Hawaii and have a coconut-shell bikini,” she explains. “Man-made manufacturing is coming into play. That means at some point the material doesn’t exist as a fiber but as a goo broken down by chemicals, which is then shot out through spinnerets to harden into a textile form.”

Consequently, brands cannot use a natural name when listing the fiber content. “They must use the name the FTC has recognized,” Felix says. “It tells consumers this is not actual soy, corn or bamboo, it’s rayon. And there is a distinction.”