When COVID-19 ground everyday life to a halt, the impact on the retail industry was immediate and severe. The fashion industry, which offers anywhere from twelve to many dozens of deliveries per year, was left staggering as the pandemic forced far-flung overseas factories to shut down. Orders were cancelled, or retailers and brands refused to pay for completed goods because sales nosedived as stores were ordered to close. During the ensuing months, the havoc wrought by the coronavirus has generated discussions about the practicality of near-shoring business, and perhaps creating a “revolution” in U.S. manufacturing.[quote]

The CFDA’s Cal McNeil, program manager, explains in an interview with the Lifestyle Monitor™ how the turbulence in the early days of the coronavirus led brands into unmapped territory.

“Before New York City and much of the United States transitioned to lockdown, designers I spoke with decided to either keep their production with their international manufacturing partners and hope those countries had short lockdowns, or decided to pull their production and send it elsewhere, including New York and other U.S. manufacturing hubs,” McNeil says in the interview. “In the end, because New York was swift in locking down and mandating the closure of manufacturing and other businesses, those designers who pulled their overseas production to New York City didn’t end up with much more benefit than those who kept their inventory elsewhere — other than having their materials and products in-hand.”

A staggering 98 percent of clothes and shoes purchased in the U.S. are imported, according to a Sourcing Journal op-ed from the American Apparel and Footwear Association’s Stephen Lamar, executive vice president. China accounts for 41 percent of the apparel imports, followed by countries that include India, Vietnam, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. For overseas manufacturers, the lockdown led to immediate financial burdens and impacted cash flow, McNeil says, stemming from paused current projects, overdue invoices on completed and delivered work from designer clients, and no new incoming work.

All of this industry upset has led to an uptick in talk about manufacturing locally in places like New York, Detroit, and Los Angeles, McNeil says in the interview.

Nearly 72 percent of consumers say it’s important to them to support local businesses during this time, according to the Cotton Incorporated 2020 Coronavirus Consumer Response Survey (Wave II). And more than 6 in 10 consumers (61 percent) say they want to spend money in order to help reboot the economy.

Despite these good intentions, Forrester estimates global retail will lose $2.1 trillion in 2020, a reduction so steep it will take four years before stores recover to pre-pandemic levels. If four years seems long, consider that a report from Business of Fashion and McKinsey & Company values the annual global fashion industry at $2.5 trillion.

In the interview, McNeil says the interest in nearshoring is multi-faceted, starting with wanting more control over their products and supply chains.

“If the product is closer, it is easier to access in case of another coronavirus resurgence or lockdown,” he says, allowing for quicker turnaround for e-commerce/direct-to-consumer sales, which many brands have increased within their distribution strategy. Also, “their production runs are smaller because of slashed orders from retailers. So local manufacturing makes more sense financially. Also, their overseas partners can’t accept small runs.”

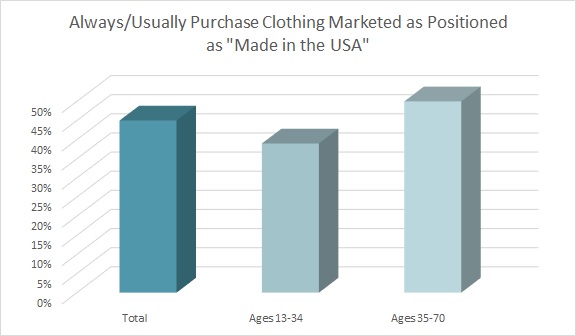

Nearly half of all consumers (47 percent) say that whether or not a clothing item is made in the U.S. is important in their apparel purchase decisions, according to the Cotton Incorporated’s Lifestyle Monitor™ Survey. And 45 percent say they “always/usually” purchase clothes marketed as Made in the USA according to the Monitor™ survey.

Forrester’s Brendan Witcher, vice president and principal analyst, said in a recent webinar that he believes a lot of stores will review what and when COVID-related breakdowns occurred in their supply chains.

“The question I would pose to the retail industry is, ‘Will you do something?'” he asked. “There’s been a lot of discussion about COVID coming back, God forbid, in October, November or December of this coming year. And I wonder how many retailers are going to say, ‘Okay, the supply chain is where we need to fix it.’ And I don’t think they will. I’m not trying to insult anybody by saying this.

“But I think what’s going to end up happening is retailers are going to take a look and say, ‘We missed on our top line number, we missed on our bottom line number. We’ve got to do what we can to try to make up those numbers by the end of the year,” Witcher stated. “And we’re going to see a lot of companies shifting dollars out of investment in technology and things like that, and moving it into marketing to try to win back those customers. If we go through this again, and if it’s worse than it was this time, I do worry that supply chains might not be able to handle it again — and it might be even worse.”

McNeil says in the interview that U.S. fashion manufacturers can “currently and easily” cater to small-to-medium sized luxury-level designers. And some higher production runs can be done for more simple patterns and products. Technology, he says, is crucial to increasing the capabilities and scale that would be necessary to compete with overseas manufacturers.

“The CFDA’s Fashion Manufacturing Initiative (FMI) has focused on technology acquisition through our FMI Grant Fund, which has invested over $3.5 million with most going towards investment in machinery and software to help introduce new services, continue to improve quality and help scale production with better efficiency to New York City’s fashion manufacturing sector,” McNeil says in the interview.

The industry has also speculated about shifting delivery calendars to closer or in-season models. McNeil says if that happens, domestic manufacturing will become critical, as will adapting to newer models for manufacturing — such as on-demand or just-in-time manufacturing — as well as continued investment in advanced technology and training to increase efficiency.

Software company Blue Yonder also points out that supply chain management technology will be crucial going forward.

“Once the chaos began… too many businesses relied heavily on suppliers that were single-source and based halfway around the world,” Blue Yonder states. “Therefore, it is important to ensure that fundamental supply chain strategies are in place, such as having an appropriate mix of strategic supplies for critical raw materials, enabling end-to-end visibility and ensuring a good process orchestration.”

The firm recommends technology that would offer users “control tower” views of their business, as well as leverage AI and machine learning to see what is happening in the supply chain — and recommend remedial measures through predictive analytics.

In the interview, McNeil says 2020 may be one of the hardest years that the industry has had to navigate.

“The entire chain dissolved within a matter of weeks because of the pandemic,” he says. “Retailers collapsed with too much inventory and no consumer shopping, which then led to retailers cancelling or drastically decreasing future orders, or not having the ability to pay designers on recent deliveries. Designers then did not have funds on hand and could not pay their manufacturers, other vendors and even their own teams.

“The type of brands manufacturing in the U.S. could change because some large brands have or will downsize so much that local manufacturing could make sense for them,” McNeil says. “And some brands may only be able to afford lower-priced production costs that some U.S. manufacturers can’t compete with. But I think overall the same level of brands will continue to produce locally.”