Microplastic pollution from synthetic textiles can be found all over the world — from Mount Everest, the highest point on the planet, to the Mariana Trench, the deepest oceanic trench on Earth. For eco-conscious fashion designers, retailers and brands, the concern becomes how to combat the microplastic problem – from the fabrics used to the quality of the clothes to the amount produced.

Brands need to be doing their homework. Are they getting behind those practices they say they care about and really understanding what they’re doing? Right now, any opportunity you can take to make a safer product, you should be exploring.”

Nikki Clay

Head of Men’s Global Sales, DL1961

Within fashion, the microplastic problem stems from the heavy use of synthetics like polyester, acrylic, and nylon. Such manmade, petroleum-based materials account for 69 percent of all textile fibers. It takes approximately 342 million barrels of oil each year to produce synthetic fibers, according to BBVA’s OpenMind research. The microfibers from these petroleum-based clothes enter the environment during production, use, and even end of life, as 85 percent of textile waste ends up in landfills. Unlike natural fibers, which biodegrade over time and return to the Earth, petroleum-based clothes will not decompose for decades if not hundreds of years, allowing the microfibers to blow through the air and enter the soil, air, and water. Further, if synthetic clothes are incinerated with landfill trash, the fibers can emit pollutants into the atmosphere.

Timo Rissanen, a fashion and textiles researcher, and associate professor at the University of Technology Sydney, Australia, said it is technically possible for the fashion industry to combat the global microplastic problem by switching to natural fibers, but shifting the business mindset and the value systems underlying fashion are where the challenges lie.

“Fibers derived from petrochemicals have created the illusion that there are no concrete limits to the volumes of clothing we produce today, and that’s a dangerous illusion,” Rissanen says in an interview with the Cotton Incorporated Lifestyle Monitor™. “Limitless growth is a suicidal fantasy. Also, the problem with petrochemical-based fibers is two-fold: it is a problem of extraction and a problem of plastic pollution, including microplastic pollution. Show me a site of oil or gas extraction that is somehow ‘ethical’ or ‘neutral.’ We in fashion are complicit.”

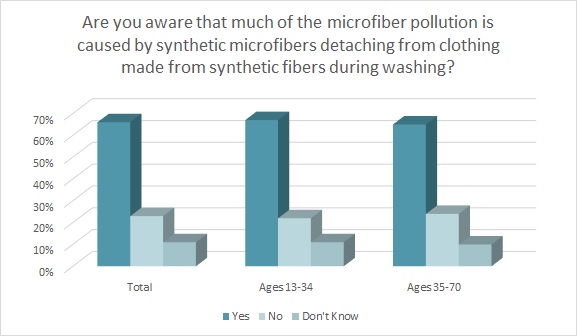

This close relationship with petroleum-based apparel could prove increasingly problematic as consumers become more environmentally concerned. The majority of consumers (66 percent) who are aware of microplastic pollution know that much of it is caused by washing clothes made of synthetic fibers, according to the 2022 Cotton Incorporated Lifestyle Monitor™ Survey. And nearly two-thirds of shoppers (65 percent) who are aware of microfiber pollution say this awareness will affect their future clothing decisions. Even more, 63 percent are bothered by brands and retailers using synthetic fibers in their clothing because of plastic microfiber pollution.

Premium denim brand DL1961 – tagline: “The Circular Denim Company” — has partnered with Recover, a post-consumer textile sciences company and global producer of low-impact, high-quality recycled cotton fiber and cotton fiber blends. Going into 2023, every product in DL1961’s line will contain Recover recycled cotton fibers.

Three-fourths of consumers (75 percent) say they are interested in apparel recycling as a sustainability initiative for the fashion industry, according to the Monitor™ research. And nearly one-third of consumers (34 percent) say they are willing to pay more for clothing produced via clothing recycling. Further, about a third say they are interested in clothing recycling programs that recycle old clothes into new apparel (34 percent).

“Working with Recover is another step in our pursuit of better, and that’s what we stand for when it comes to sustainability and being transparent,” said DL1961’s Nikki Clay, head of men’s global sales, at the recent PROJECT New York trade show in an interview with the Monitor™.

When it comes to combatting microplastic pollution, Clay says, “Brands need to be doing their homework. Are they getting behind those practices they say they care about and really understanding what they’re doing? Right now, any opportunity you can take to make a safer product, you should be exploring. And if people understand costs, if you educate your consumer on why your product is more expensive, then you give them information to help them with their decision.”

Over a third of consumers (49 percent) say sustainability or environmental friendliness is important to them when deciding what clothing they plan to purchase, according to Monitor™ research. Further, nearly half of all consumers (47 percent) say that the term ‘sustainable clothing’ means long-lasting or durable, followed by environmentally friendly (23 percent), renewable/reusable (18 percent), and natural/safe (7 percent). Most say cotton clothing is the most sustainable (76 percent), highest quality (71 percent), and lasts the longest (59 percent) compared to manmade fiber clothing.

Håndvaerk’s Esteban Saba, co-founder and CEO of the Southampton, NY-based apparel brand, said his company, which uses only natural fibers, is the “poster child for slow fashion.”

“I think making less clothes, making things that are less seasonal, making clothes that are meant to last… this is the long-term answer,” Saba said at the recent Man/Woman trade show in New York in an interview with the Monitor™. “I think there’s a very young consumer that’s very ideological in what they talk about, but there might be a money obstacle so they’re going to these fast fashion brands. For us, our consumer is the working professional who can invest in something that’s meant to last, who likes quality. He’s not looking for the next trendy thing; he’s looking for something that’s well made.”

Saba’s remarks echo the sentiment behind a proposed package of legislative measures proposed by the European Commission, which aims to make sustainable textiles the norm in the E.U. The strategy will encourage a shift toward quality, durability, longer use, repair and reuse, and will address the unintentional release of microplastics from textiles. Rissanen’s outlook jibes with such measures, as he states there needs to be both a new generation of fibers to replace conventional synthetics like polyester, as well as a reduction in the current volume of clothing that is produced.

“This is an incredibly difficult project that requires some centralized, international work and a lot of locally specific work around the world,” Rissanen says. “The fiber mix can include recycled fibers although plastic fibers that are incompatible with biological systems should be excluded, including recycled polyester, as these still contribute to microplastic pollution. Where the performance qualities of plastic polyesters are required, renewable and biodegradable fibers need to be developed and made available. What continuously concerns me is our general willingness to pump out ever more microplastics when we do not know their full impacts on human health and other organisms’ health. It speaks to a deep disconnect we have with Earth and with ourselves.”