So, you consider yourself to be environmentally conscious and do your best to make healthy food choices. However, did you know that your clothes might be coming from deforested tropical rainforests and may also be harmful to marine life? This is clearly harmful on multiple levels. But in a tight retail environment — one where a hashtag like #droughtshaming can spread like wildfire — apparel brands have a vested interest in understanding consumers’ eco concerns, and how fabric choice could impact their business.[quote]

Most consumers want to do right by Mother Earth. For example, the majority (64 percent) say they always or usually recycle, use refillable bottles (55 percent) and purchase energy-saving appliances (53 percent) in an effort to protect the environment, according to the Cotton Incorporated Lifestyle Monitor™ Survey. But just 16 percent check corporate environmental policies before making a purchase.

However, companies shouldn’t take that to mean shoppers don’t care.

“Many people, even those in the apparel business, have no idea the rayon they’re using might be coming from a tropical rainforest,” says Brihannala Morgan, senior forest campaigner with the Rainforest Action Network (RAN). RAN created the Out of Fashion campaign to demand the fashion industry commits to “getting rainforest destruction and human rights abuses out of our clothing.”

The fast-growing trees from rainforests are harvested and the wood is mixed with toxic chemicals to form a slurry — also known as dissolving wood pulp — that’s forced through spinnerets, producing viscose staple fiber. This is then woven into synthetic fabrics for apparel. Not all dissolving wood pulp comes from conflict rainforests. RAN works with influential apparel companies — like Ralph Lauren — to create responsible supply chain policies.

As a natural fiber, cotton is biodegradable. The Environmental Protection Agency’s Julia Valentine, spokesperson, explains how clothes made of a synthetic fabric like polyester and nylon can end up as microplastic in lakes, rivers and, ultimately, the world’s oceans.

“Synthetic fabrics are made partly or wholly from plastic polymers. In addition to the fact that these polymers are made from petroleum, synthetic fabrics may also degrade or break down during everyday use and laundering to produce synthetic microfibers,” Valentine says, explaining that microfibers are those less than 5 millimeters in size in any dimension. “These microfibers do not biodegrade in the environment like natural fibers do, and researchers have found that microfibers are widespread in the marine environment and in the Great Lakes. Aquatic animals are also known to ingest these microfibers, but the impacts of this ingestion are not yet well understood. Worldwide monitoring is showing that microplastics exist in all of the world’s oceans and may pose health and ecological hazards.”

Fish and other wildlife can easily consume the tiny synthetic fibers. The Guardian reported that the microfibers “have the potential to bioaccumulate and concentrate toxins in the bodies of larger animals, higher up the food chain.” The Guardian also reported that researcher Chelsea Rochman determined in a study of seafood from California and Indonesia that “the food we eat is contaminated with plastic fibers.”

After being educated about deforestation and microfiber waste issues, 66 percent of consumers say they’re bothered that brands and retailers are using synthetic fibers in their apparel, according to Monitor™ data. Of all the fiber-related issues, deforestation to create rayon fibers (31 percent) is the most concerning to consumers, followed by microfiber waste from synthetics filling up the world’s oceans (25 percent).

Morgan explains that most of the wood pulp for synthetics comes from rainforests in four countries: Indonesia, Brazil, Canada, and South Africa. But the area most conflicted is Indonesia.

“Companies that produce viscose staple fiber rely on fast-growing trees like eucalyptus and acacia,” Morgan says. “They grow the fastest in tropical regions.”

Indonesia is home to the Leuser Ecosystem, which RAN describes as the last place on Earth where Sumatran orangutans, elephants, tigers, rhinos, and sun bears roam the same habitat. The Leuser is also filled with carbon-rich peatlands. RAN states that when these areas are drained and clear cut, and the peat is exposed to air, it begins to oxidize. This releases large amounts of carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere, a process that continues for decades. The dried peat is also highly flammable, and last year “killer haze” from peatland wildfires was responsible for 90,000 early deaths, according to researchers from Harvard and Columbia.

Indigenous communities that live in Indonesia’s rainforest areas are also affected by the wood pulp companies.

“In Indonesia, the government doesn’t know or have maps that show where the community-owned land is,” Morgan says. “So there are communities that have used land that’s recognized by neighbors and individuals, but they don’t have a legal piece of paper for it, and they never needed it. But then the government plans out a plantation, gives licenses to a company and says the company owns the land.

“What happens is the military police come in, say the company owns the land and everyone who was living there must leave,” she says. “These are land-dependent communities. They’re farmers. And they’re losing their livelihood, access to food and water — it’s absolutely devastating.”

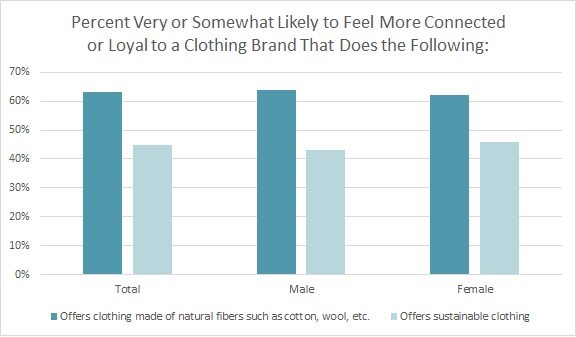

After being educated about the microfiber waste issue, 3 of 5 consumers (60 percent) say they are likely to check the fiber content label before purchasing clothing to avoid synthetics, according to Monitor™ data. Even before learning about the environmental issues with synthetics, 73 percent of consumers say better quality garments are made from all natural fibers like cotton, and 65 percent are willing to pay more for natural fibers. What’s more, 63 percent are very or somewhat likely to say they would “feel more connected or loyal” to a brand that offers clothes made of natural fibers, followed by those that offer sustainable apparel.

“We hear from consumers every day,” RAN’s Morgan says. “We have a large list of people who self-identify as caring about diversity, climate rights, deforestation. And when we told them of the connection between rayon and deforestation, we had hundreds of thousands taking part in our campaign saying they didn’t want companies they bought clothes from involved in it.”