Online shopping has been the stuff of wardrobe inspiration, late night impulse buys and time saving purchases for consumers around the world. While it stands to grow exponentially in the next five years, there are those who believe major change is necessary to help protect both the environment as well as traditional brands and retailers from certain ecommerce practices.

This represents a rare and critical opportunity to drive transformative change in the U.S. textile sector – an opportunity that is uniquely important given the limited chances to secure substantial funding for such initiatives, a chance we missed with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA).

Rachel Kibbe, CEO, American Circular Textiles

In 2019, the U.S. ecommerce market was valued at $539 billion, according to Statista. These numbers kept growing through the pandemic and continued upward despite recession fears, to the point it is estimated online shopping will generate $1.2 trillion in revenue in 2024. By 2029, U.S. ecommerce is forecasted to reach $1.9 trillion.

That all sounds like good news, so what’s the glitch? As Statista points out, “The United States has always been dominated by domestic online retailers, but now, two foreign companies are taking on the U.S. market: Temu and Shein.”

Along with other online retailers, the two China-based retailers have benefitted from the de minimis rule, which allows imports valued up to $800 per person per day to enter the U.S. free of tariffs.

“Changing or eliminating the de minimis rule may benefit traditional retailers that play by the traditional rules by leveling the playing field,” said Jon Devine, senior economist in Cotton Incorporated’s corporate strategy and program metrics division. “Traditional retailers that import through traditional channels pay the tariffs that were assigned to products.

“There are also significant environmental considerations,” Devine continued. “The focus on cheap, potentially low-quality goods suggests that garments purchased through the de minimis channel will not be worn often and consumers will quickly look for the next trend. Low prices can encourage overconsumption. Transport for de minimis goods also comes with important environmental costs. Data from Customs and Border Protection indicate that more than 90 percent of de minimis shipments arrive in the U.S. by air. Traditional imports aggregate large shipments on cargo ships, which can spread energy consumption over a wide collection of goods and therefore involve a relatively low environmental impact on a per item basis. In contrast, smaller shipments are delivered by plane to fulfill de minimis orders. This implies much higher environmental costs, particularly in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.”

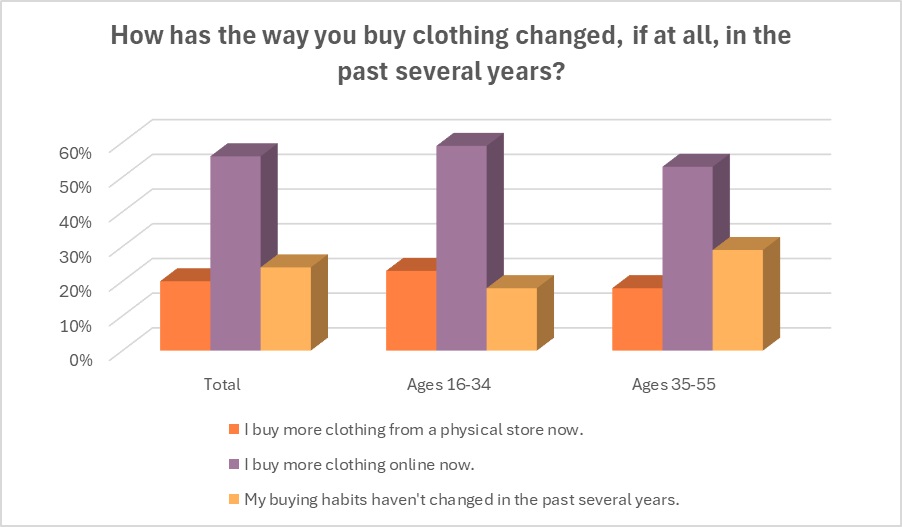

These factors no doubt have a growing impact, especially as more than half of all worldwide consumers (56 percent) say they buy more clothing online now than they have in the past several years, according to Cotton Incorporated 2023 Global Lifestyle Monitor™ Survey. Increasingly, consumers say they choose online clothes shopping for its convenience/ease (65 percent), prices (48 percent), selection/styles available (47 percent), fast shipping (41 percent), and ease of finding a size/fit (34 percent), according to Cotton Incorporated’s 2023 Online Shopping Survey.

But industry experts say these conveniences come at a cost. Dr. Sheng Lu, professor at the University of Delaware’s department of fashion and apparel studies, characterizes that the de minimis rule has provided a loophole that has become common practice. “For example, U.S. textile industry representatives argued that ‘The loophole has not only fueled the rise of imports from foreign ecommerce companies and mass distributors, but it has also put our domestic manufacturers and workers at a competitive disadvantage.’”

Rachel Kibbe, CEO at American Circular Textiles, agreed that closing the de minimis threshold is a significant step towards addressing the impact of low-value imports on domestic industries.

“However, this measure alone is insufficient if not paired with dedicated funding aimed at reinvigorating U.S. manufacturing and advancing circularity,” Kibbe told the Monitor™ in an interview. “This represents a rare and critical opportunity to drive transformative change in the U.S. textile sector – an opportunity that is uniquely important given the limited chances to secure substantial funding for such initiatives, a chance we missed with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA).”

Consideration for such investment comes as Temu and Shein continue to increase competition. It’s estimated Temu will reach $37 billion in annual sales this year, according to Backlinko, an SEO training and blog company. Currently, Temu has 50.4 million active users in the U.S., more than 167 million worldwide and claims 17 percent of the U.S. discount store category. Shein, meanwhile, has captured 50 percent of the U.S. fast fashion market, according to Statista. It has about 89 million active shoppers, with 17 million in the U.S. Earlier this year, Shein was valued at $68 billion.

Devine said the business model for de minimis shippers is built on price. This drives a race to the bottom on cost, which can imply heavier use of fibers like polyester.

“However, an emphasis on price also reduces attention to quality,” Devine said. “Goods bought from these retailers can have challenging return policies and may result in garments that are paid for but are seldom worn. In an economic environment where consumers are looking for value, low-cost items that aren’t worn do not present a great deal for consumers, despite their low prices.”

Consumers in the U.S. receive an average of seven packages a month from online retailers, three of which are apparel, according to the 2023 Online Shopping Survey. All told, shoppers bought an average of 27 clothing items online last year and returned just two garments to the retailer.

To help stem the flow of cheap fashion goods, it’s worth noting that changes to de minimis rules and thresholds have already begun.

“South Africa implemented a ban early in 2024,” Devine pointed out. “The EU is looking into it. In the U.S., there was a bill introduced in the House on de minimis shipments. Discussions surrounding the release of the bill highlighted how de minimis shipments circumvent legislation designed to reduce the importation of products made with forced labor and how de minimis shipments can allow deliveries of products that are harmful for consumers – like fentanyl. More recently, a bipartisan group of senators proposed a new law to limit de minimis shipments. It remains to be seen when these efforts will be implemented or become law.”